11 KiB

Git Contributors Guide

If you're a developer who wants to work on the SilverStripe source code and submit your changes for consideration to be merged into the master branch, here's how. In case you're after a general overview on how you can contribute to SilverStripe, see our "Contributing" guide.

Quickfire Do's and Don't's

If you aren't familiar with git and GitHub, try reading the "GitHub bootcamp documentation". We also found the free online git book and the git crash course useful. If you're familiar with it, here's the short version of what you need to know. Once you fork and download the code:

-

Don't develop on the master branch. Always create a development branch specific to "the issue" you're working on (mostly on open.silverstripe.org). Name it by issue number and description. For example, if you're working on Issue #100, a

DataObject::get_one()bugfix, your development branch should be called 100-dataobject-get-one. If you decide to work on another issue mid-stream, create a new branch for that issue--don't work on both in one branch. -

Do not merge the upstream master with your development branch; rebase your branch on top of the upstream master.

-

A single development branch should represent changes related to a single issue. If you decide to work on another issue, create another branch.

-

Squash your commits. After you rebase your work on top of the upstream master, you can squash multiple commits into one. Say, for instance, you've got three commits in related to Issue #100. Squash all three into one with the message "Issue #100 Description of the issue here." We won't accept pull requests for multiple commits related to a single issue; it's up to you to squash and clean your commit tree. (Remember, if you squash commits you've already pushed to GitHub, you won't be able to push that same branch again. Create a new local branch, squash, and push the new squashed branch.)

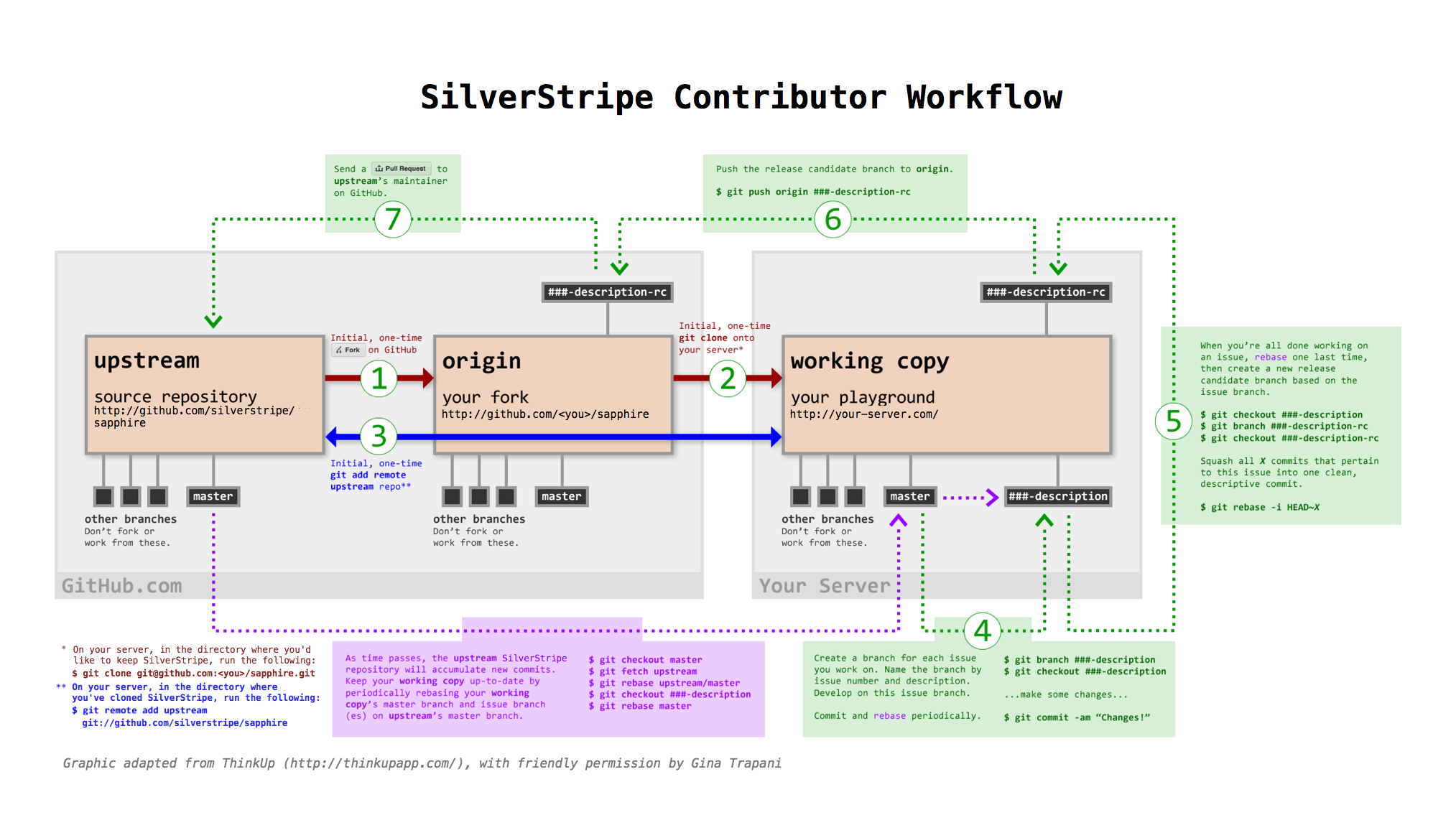

Workflow Diagram

Step-by-step: From forking to sending the pull request

- Follow the "Installing from source" ("Option 2: Installation for contributions"), which explains how to fork the core modules and add the correct "upstream" remote

- Branch for new issue (

git branch ###-description; git checkout ###-description</code>) and develop on issue branch. _As time passes, the upstream repository accumulates new commits. Keep your working copy's master branch and issue branch up to date by periodically rebasing: fetch upstream, rebase master, rebase issue branch (<code>git fetch upstream; git checkout master; git rebase upstream/master; git checkout ###-description; git rebase master - When development is complete, rebase one more time, then branch from dev branch to release candidate branch (

git checkout ###-description; git branch ###-description-rc; git checkout ###-description-rc</code>). Squash all _X_ commits that pertain to the issue into one clean, descriptive commit (<code>git rebase -i HEAD~X - Push release candidate branch to GitHub (

$ git push origin ###-description-rc) - Issue pull request on GitHub (Click Pull Request button)

Create an Issue-Specific Development Branch

Before you start working on a new feature or bugfix, create a new branch dedicated to that one change named by issue number and description. If you're working on Issue #100, a retweet bugfix, create a new branch with the issue number and description, like this:

$ git branch 100-dataobject-get-one

$ git checkout 100-dataobject-get-one

Edit and test the files on your development environment. When you've got something the way you want and established that it works, commit the changes to your branch on your local git repo.

$ git add <filename>

$ git commit -m 'Issue #100: Some kind of descriptive message'

You'll need to use git add for each file that you created or modified. There are ways to add multiple files, but I highly recommend a more deliberate approach unless you know what you're doing.

Then, you can push your new branch to GitHub, like this (replace 100-dataobject-get-one with your branch name):

$ git push origin 100-dataobject-get-one

You should be able to log into your GitHub account, switch to the branch, and see that your changes have been committed. Then click the Pull button to request that your commits get merged into the development master.

IMPORTANT: Before you issue a pull request, make sure it gets accepted by running through the "Contributing Check List".

Rebase Your Development Branch on the Latest Upstream

To keep your development branch up to date, rebase your changes on top of the current state of the upstream master. See the What's git-rebase? section below to learn more about rebasing.

If you've set up an upstream branch as detailed above, and a development branch called 100-dataobject-get-one, you'd update upstream, update your local master, and rebase your branch from it like so:

$ git fetch upstream

$ git checkout master

$ git rebase upstream/master

$ git checkout 100-dataobject-get-one

# [make sure all is committed as necessary in branch]

$ git rebase master

You may need to resolve conflicts that occur when a file on the development trunk and one of your files have both been changed. Edit each file to resolve the differences, then commit the fixes to your development server repo and test. Each file will need to be "added" before running a "commit."

Conflicts are clearly marked in the code files. Make sure to take time in determining what version of the conflict you want to keep and what you want to discard.

$ git add <filename>

$ git commit

To push the updates to your GitHub repo, replace 100-dataobject-get-one with your branch name and run:

$ git push origin 100-dataobject-get-one

Squash All Commits Related to a Single Issue into a Single Commit

Once you have rebased your work on top of the latest state of the upstream master, you may have several commits related to the issue you were working on. Once everything is done, squash them into a single commit with a descriptive message (see "Contributing: Commit Messages").

To squash four commits into one, do the following:

$ git rebase -i HEAD~4

In the text editor that comes up, replace the words "pick" with "squash" next to the commits you want to squash into the commit before it. Save and close the editor, and git will combine the "squash"'ed commits with the one before it. Git will then give you the opportunity to change your commit message to something like, "BUGFIX Issue #100: Fixed DataObject::get_one() parameter order"

Important: If you've already pushed commits to GitHub, and then squash them locally, you will not be able to push that same branch to GitHub again. Create a new branch--like 100-dataobject-get-one-squashed or 100-dataobject-get-one-rc1 (for "release candidate 1") - and squash your commits there. Once everything is squashed and ready, push the new squashed branch to GitHub and send your pull request to Gina.

Helpful hint: You can always edit your last commit message by using:

$ git commit --amend

Some gotchas

Be careful not to commit any of your configuration files, logs, or throwaway test files to your GitHub repo. These files can contain information you wouldn't want publicly viewable and they will make it impossible to merge your contributions into the main development trunk.

Most of these special files are listed in the .gitignore file and won't be included in any commit, but you should carefully review the files you have modified and added before staging them and committing them to your repo. The git status command will display detailed information about any new files, modifications and staged.

$ git status

One thing you do not want to do is to issue a git commit with the -a option. This automatically stages and commits every modified file that's not expressly defined in .gitignore, including your crawler logs.

$ git commit -a

What's git-rebase?

Using git-rebase helps create clean commit trees and makes keeping your code up-to-date with the current state of the upstream master easy. Here's how it works.

Let's say you're working on Issue #212 a new plugin in your own branch and you start with something like this:

1---2---3 #212-my-new-plugin

/

A---B #master

You keep coding for a few days and then pull the latest upstream stuff and you end up like this:

1---2---3 #212-my-new-plugin

/

A---B--C--D--E--F #master

So all these new things (C,D,..F) have happened since you started. Normally you would just keep going (let's say you're not finished with the plugin yet) and then deal with a merge later on, which becomes a commit, which get moved upstream and ends up grafted on the tree forever.

A cleaner way to do this is to use rebase to essentially rewrite your commits as if you had started at point F instead of point B. So just do:

git rebase master 212-my-new-plugin

git will rewrite your commits like this:

1---2---3 #212-my-new-plugin

/

A---B--C--D--E--F #master

It's as if you had just started your branch. One immediate advantage you get is that you can test your branch now to see if C, D, E, or F had any impact on your code (you don't need to wait until you're finished with your plugin and merge to find this out). And, since you can keep doing this over and over again as you develop your plugin, at the end your merge will just be a fast-forward (in other words no merge at all).

So when you're ready to send the new plugin upstream, you do one last rebase, test, and then merge (which is really no merge at all) and send out your pull request. Then in most cases, we have a simple fast-forward on our end (or at worst a very small rebase or merge) and over time that adds up to a simpler tree.

More info on the "Rebasing" chapter on progit.org and the git rebase man page.

Related

License

This guide has been adapted from the "Thinkup" developer guide, with friendly permission from Gina Trapani/thinkupapp.com.